Keith Ellisons Plan for Democrats to Win Again You Tube

Chris Visions

Last May, equally Donald Trump was locking up the Republican nomination, a prophetic clip began circulating amidst portions of the left. It was a nearly i-twelvemonth-old segment of ABC's Sun testify This Week, featuring Rep. Keith Ellison, the Minnesota Democrat and then on the verge of winning a sixth term. "Anybody from the Democratic side of the fence who'southward terrified of the possibility of a President Trump better vote, amend get active, better get involved," Ellison warned, "because this man has got some momentum and nosotros improve be ready for the fact that he might exist leading the Republican ticket."

Ellison made his prediction in July 2015, shortly after Trump had launched his campaign by calling Mexican immigrants "rapists." His fellow panelists laughed forth with moderator George Stephanopoulos, who offered Ellison a lifeline. "I know you don't believe that," he said. But Ellison insisted, "Stranger things have happened."

Now, Trump is president, and Ellison, who saw it coming, is afterwards a new job: running the Democratic Party. He appear his candidacy for Democratic National Committee chair in mid-November, and he and former Labor Secretarial assistant Tom Perez are the front-runners for the position, which the well-nigh 450 members of the DNC will vote on in belatedly February. Ellison, an early and vocal supporter of Bernie Sanders who campaigned hard for Hillary Clinton last fall, is running to unify a fragmented political party. Sanders backs him. So do Sens. Elizabeth Warren and Chuck Schumer, the Democratic minority leader. So does the AFL-CIO. Win or lose, the 53-yr-old Ellison, a Muslim, African American co-chair of the Congressional Progressive Caucus, is poised to hold a position of influence in the party during one of the darkest moments in its history. Democrats are out of the White Business firm and in the minority in Congress, and they've lost their window to reshape the Supreme Courtroom. They control both the governor's mansion and legislature in only vi states; with another round of redistricting looming, the electoral map is just poised to go worse.

The part of the DNC chairman is to run a political machine that helps to elect Democrats throughout the state, not to dictate the party's policy priorities. But Ellison's design for defeating Trumpism is nonetheless rooted in the anti-establishment politics of Sanders. The DNC has become the "Democratic Presidential Committee," he argues; short-sighted focus on large-dollar fundraising and swing states has weakened the party on a county-past-canton level. Change starts with shifting the party appliance toward assembling a multicultural army of organizers, focused on the communities likely to bear the full brunt of the new president's policies. Ellison says the proof that this tin can work is in his commune. Emphasizing door-to-door engagement over Tv ad, Ellison boasts he's juiced turnout in his prophylactic Autonomous seat to some of the highest levels in the country. Even as the Upper Midwest goes red, Minnesota Democrats have scored victories at the state level, bolstered by Ellison's Minneapolis machine.

Many Democrats underestimated the extent to which Trump'south religious intolerance and ravings nigh "inner cities" would appeal to broad, largely white swaths of the electorate. Ellison, who congenital his career contesting racist institutions, knew improve than to make that mistake.

Republicans are eager to take him on, considering in many ways, the story of Keith Ellison is the story conservatives wanted to believe about another cerebral African American community organizer from the Midwest—Barack Obama. Raised Catholic in Detroit, Ellison converted to Islam, dabbled in black nationalism, and marched with the Nation of Islam'south Louis Farrakhan—all before his first bid for Congress in 2006. His past indomitable him in that run, and it has continued to be an issue in the DNC race: Billionaire Haim Saban, one of the Democrats' biggest donors, has trashed him every bit an "anti-Semite."

As a young activist in Minneapolis, Ellison learned to build coalitions outside the scope of political party politics. He too learned the limits of what such activism could reach without political power. For Ellison, it was a time of experimentation, education, and sometimes radical dalliances that ultimately imbued in his politics a hard-edged pragmatism. Many Democrats underestimated the extent to which Trump's religious intolerance and ravings near "inner cities" would entreatment to broad, largely white swaths of the electorate. They banked on the arc of progress to knock him back. Ellison, who built his career contesting racist institutions, knew better than to brand that error.

Ellison was the third of v boys raised in a big brick house in a mixed-race enclave of Detroit known as Palmer Woods. His father, Leonard Ellison Sr., was a psychiatrist, an atheist, and a difficult-ass who quizzed his sons on current events and drove them to Gettysburg to walk the battlefield every Easter. Leonard was a Republican, not an activist. While he once helped to integrate a sailboat race run by an all-white Detroit yacht club, he by and large believed in nudging a racist system through relentless achievement. The Ellison boys were expected to go either doctors or lawyers. They all did.

If his trajectory was ordained past his father, Ellison's worldview bore the imprint of his mother, Clida, a devout Catholic from a Louisiana Creole family unit. The congressman's maternal grandfather was a voting rights organizer in Natchitoches. Clida was sent to a boarding school for safety; the Ku Klux Klan once burned a cross outside their house. Clida's family tree—with roots in the Balkans, France, Kingdom of spain, and W Africa—was a prism for understanding the absurdity of the South's racial caste system. Ellison's younger brother, Anthony, at present a lawyer in Boston, recalled Ellison struggling with their mother'due south revelation that some of their Creole ancestors had owned slaves. During visits to a family cotton farm in Louisiana, Ellison brought notebooks and a tape recorder and spent hours interviewing relatives.

Ellison'due south political awakening, which he credits to reading The Autobiography of Malcolm X at age 13, came during a period of racial turmoil in Detroit. When riots started after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., Ellison, then five, hid under his bed as National Guard personnel carriers cruised past his block. Over a two-and-a-one-half-year period in the early 1970s, i Detroit police unit that formed afterwards the riots was accused of killing 21 African Americans. Ellison feared crime and the people tasked with stopping information technology. Later on graduating from high schoolhouse in 1981, he majored in economics at nearby Wayne State Academy, moving out of his leafy neighborhood and into a 1-chamber apartment in the city's fissure-ravaged Cass Corridor.

Ellison's showtime brush with controversy came a few months into his freshmen year. After joining the educatee newspaper, the South End, he persuaded the editor to publish a drawing featuring v identical black men dribbling a basketball alongside a man in a Klan robe who was clutching a lodge. Above it was a question: "How many Honkies are in this picture?" It was meant to poke fun at racial caricatures, but students didn't see the humor. An African American classmate stormed into the newspaper'due south office to confront him—a scene Ellison breezily recounted in a follow-up column mocking the outcry. His critics were "still living in the Jim Crow era," Ellison wrote. The firestorm fabricated the pages of the Detroit Free Printing.

In the months to follow, friends noticed a change in Ellison. "He seemed to be a footling more introspective, a trivial more attentive," says Mary Chapman, a Detroit writer who worked on the South End. "Maybe he grew upward."

Or maybe he establish religion. Ellison had drifted from his mother's Cosmic church, just it had left a void. In his 2014 memoir, My Country, 'Tis of Thee, Ellison writes that he began attention a mosque when he was 19—drawn by a billboard he passed on his commute. Clida Ellison described the reveal as more disruptive than shocking. "He announced one day that he was going to mosque," she said, "and my next question was: 'What'due south mosque?'"

Increasingly, he devoted his energy to anti-apartheid activism, and his columns took on a new urgency. When Bernie Goetz was acquitted of attempted murder after shooting four black men on a New York City subway, Ellison warned, "[I]t won't be long before police officers, old ladies, weekend survival gamers, and everyone else considers it open season on the brothers."

He read a lot of Frantz Fanon, the Marxist anti-colonialist writer from Martinique, and in 1985 he attended a campus speech by Louis Farrakhan, the controversial Nation of Islam leader who blended calls for black empowerment with lengthy diatribes confronting Jews, gays, and other groups. "I remember talking to him and existence surprised at how far left he had gone," says Chuck Fogel, an editor at the Southward Terminate who lived side by side door to Ellison. But in that location was an air of experimentation to everything he did. In high school, Ellison had formed a short-lived ska and thrash-metal band called the Deviants. Now, Ellison would fiddle with his guitar incessantly, studying different variations of "Johnny B. Goode," Fogel recalls. Sometimes it was the Chuck Drupe version. Sometimes it was Jimi Hendrix. "He was trying on things and searching."

Many Democrats view Ellison every bit the kind of organizer the moment demands, capable of harnessing the resurgent movements of the left—racial justice and economic populism. Only critics have flogged a consistent narrative well-nigh his past, 1 that has haunted him since his get-go run for Congress in 2006. The case against Ellison has its roots in his time at the Academy of Minnesota Law School, where he began making a name for himself every bit a vehement critic of police and a Farrakhan defender. It was a radical identity he outgrew, one that friends insist doesn't represent the Ellison of today, merely one that fundamentally changed his idea of how politics worked.

Detroit had been a hub of blackness culture and political power. The Twin Cities were not. When Ellison arrived in the fall of 1987, the University of Minnesota had few tenured black professors. The state had just 1 black legislator. In an interview at the time, a young Ellison described the climate as "extremely isolating."

When the Africana Educatee Cultural Center sponsored speeches by Farrakhan and i of his assembly, tensions erupted on campus between Jews and African Americans. Ellison, who had taken to calling himself "Keith Hakim," published a serial of op-eds in the student newspaper, the Minnesota Daily, defending the Nation of Islam leader. The center likewise invited Kwame Ture, the black-power activist formerly known as Stokely Carmichael, to give a speech, during which he called Zionism a form of white supremacy. Ellison, and then a member of the Black Law Student Association, introduced him.

In the hopes of mending fences, the university organized a serial of conversations betwixt black students and Jewish groups. Ellison could be deferential at these meetings. He thanked Jewish students for sticking upwards for black students' right to host controversial campus speakers—even if they had denounced those speakers—and suggested working together on mutual political causes. Just he as well insisted the charges that Ture was racist were unfounded. Michael Olenick, a Jewish educatee who clashed with Ellison and who was the opinions editor at the Daily, recalled Ellison maintaining that an oppressed group could not be racist toward Jews because Jews were themselves oppressors. "European white Jews are trying to oppress minorities all over the world," Olenick remembers Ellison arguing. "Keith would proceed all the fourth dimension about 'Jewish slave traders.'" Some other Jewish student active in progressive politics recalled Ellison'southward incredulous response to the controversy over Zionism. "What are you lot afraid of?" Ellison asked. "Practise you think black nationalists are gonna get power and injure Jews?" (Ellison has rejected allegations of anti-Semitism. "I have always lived a politics divers by respecting differences, rejecting all forms of racism and anti-Semitism," he wrote recently. He declined to be interviewed for this story, and his office did not respond to detailed questions from Mother Jones.)

Ellison addresses the Autonomous National Convention. Mark Kauzlarich/Reuters

At police schoolhouse, Ellison was already laying a foundation for his shift to politics. He was condign known equally an organizer, with a flair for publicity. At the offset of 1989, 2 incidents solidified his growing reputation. On January 25, as part of a series of raids on suspected cleft storehouses, constabulary tossed a stun grenade through the window of an flat building in North Minneapolis. Two elderly blackness residents died in the resulting blaze. No drugs were found, and none of the men arrested at the building were later on charged. A grand jury declined to indict the offending officers.

Ellison and a few students organized a protest over the lack of prosecutions, but the 24-hour interval before their rally, some other incident happened at the downtown Embassy Suites. The hotel was a hangout spot for higher students, and on that night two parties were happening on the same floor. Ane was a kegger hosted by a grouping of white students. The other was a birthday party attended by African American students. It was a depression-fundamental gathering; ane woman had brought her toddler. But when police responded to a noise complaint about the kegger, they busted up the birthday instead.

Partygoers alleged that the cops had called them "niggers." One student at the party, a Daily reporter named Van Hayden, told me an officeholder had dangled him over the edge of the sixth-floor railing. He left in handcuffs, with a broken nose and a few hobbling ribs.

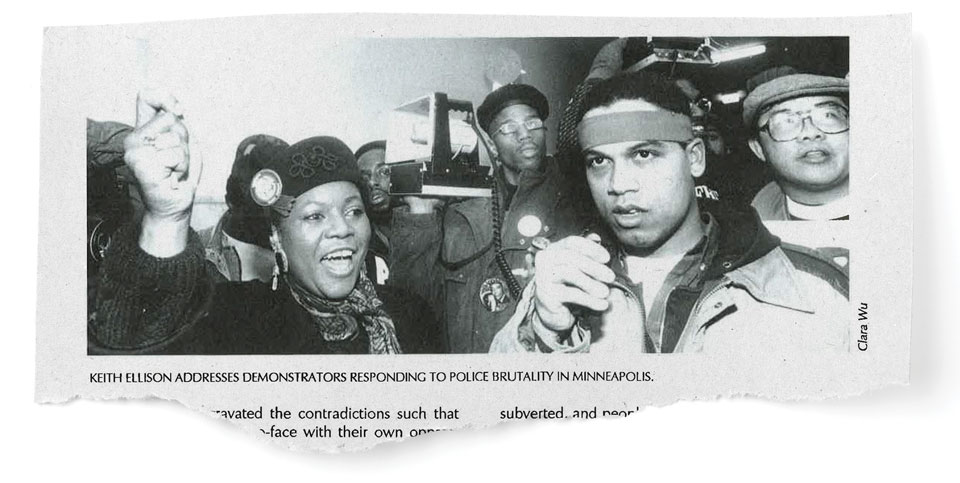

The adjacent solar day, later on the students were released, they joined Ellison at the sit-in against police brutality. A few days later, Ellison led about 75 people in a march to City Hall, where they stormed a City Council meeting, forcing officials to yield the flooring to Ellison for a ten-infinitesimal speech. Past then, Ellison was organizing several protests a week and belongings printing conferences to pressure level Minnesota'southward attorney full general to launch a state investigation into the raid. Ellison demanded "public justice." "Information technology was a mini-Ferguson before anyone had heard of Ferguson," Hayden told me.

Ellison and his main collaborator, an undergraduate named Chris Nisan who was active with the Socialist Workers Party, attracted the attention of Forward Motion, a pocket-size socialist periodical. Their interview ran with a photo of Ellison clutching a megaphone, a headband wrapped around his forehead. "People are coming face-to-face with their own oppression," Ellison said. He was alarmed past the rising of white supremacist David Duke. "Viii years of mean-spiritedness of the Reagan era have encouraged fascist and racist forces to come out again. A Ku Kluxer was just elected in Louisiana. We run across a rise in police force brutality all over the country." Ellison envisioned a unified forepart of young black people, white progressive students, organized labor, and American Indians pushing back against the evils of capitalism and white supremacy. "The more than the right attacks, the more we have to answer."

Ellison and Nisan'southward protests did win a victory, albeit a limited one. Four of the five students arrested at the hotel were acquitted of their misdemeanor charges, and Minneapolis set up an independent, if weak, review board to investigate law brutality claims. In 1990, Ellison helped launch the Coalition for Police Accountability, which organized community meetings and published a quarterly newspaper, Cop Spotter.

As the city's crime rate soared in the early '90s, some residents took to calling it "Murderapolis." Black residents institute themselves in the crosshairs of anti-offense initiatives and city politics. Ellison was still leading protests confronting the constabulary, simply he was not just on the outside. Two years out of law schoolhouse, he ran for a seat on a urban center committee that controlled $400 million in development funding. Ellison'due south slate stunned observers with its organisation, bringing in iii busloads of Hmong residents to vote in a race few people knew existed. North Minneapolis now controlled vii of eight seats.

Around this time, Ellison began attending a volume club led past a prominent history professor at Macalester Higher who placed an accent on reclamation—the idea that whatever gains African Americans made would have to come through their own efforts. "The aforementioned way that our ancestors laid something down for the states, we got to lay something down for the people who come next," is how Resmaa Menakem, a friend of Ellison's who was besides in the society, described the theme. In practice, this meant building institutions—schools, borough groups, nonprofits—capable of boosting and protecting the customs.

During Black History Month in 1993, Menakem and Ellison guest-hosted a segment on the blackness community radio station KMOJ nigh James Baldwin and Malcolm X. It evolved into a weekly bear witness called "Black Power Perspectives" that lasted for viii years. The callers forced Ellison to recall and argue on his anxiety and at times keep his emotions in check. Islam was a specially volatile subject. White supremacists frequently chosen in, and Ellison one time got then agitated he had to leave the studio.

Ellison's fiery disposition sometimes got him into trouble. Pecker English, a longtime Twin Cities activist, recalled almost coming to blows with Ellison during a nonprofit board meeting in the early aughts. "We went down to nose-to-nose, and people walked upwards to us and separated us, and a day subsequently he chosen me and apologized profusely," he says. English was nearly 70 years old at the time. During his 2012 race, Ellison and his ex-Marine Republican opponent got into an exchange on a radio bear witness so heated that the moderator interrupted to call for a commercial pause.

In 1993, afterward a pit stop at a white-shoe law house, Ellison landed a job as executive director of the Legal Rights Heart, a nonprofit focused on providing indigent defence force in the city's African American, Hmong, and American Indian communities. (One of the group'due south founders represented Russell Means and Dennis Banks after their 1973 standoff at Wounded Knee.) Ellison still didn't shy away from controversy. He partnered with a erstwhile Vice Lords gang leader named Sharif Willis to tackle police brutality—an try that fell apart when Willis held 12 people up at gunpoint at a gas station. (Ellison has chosen the brotherhood "naive.") Just he fabricated a name for himself on tough cases. His aggressive legal tactics were a lot similar his arroyo to political organizing. "Some lawyers will spend well-nigh of their fourth dimension in the back room trying to convince not only their client only also the prosecutor to make a deal—Keith was kind of the reverse," says Beak Ways, Russell's brother and an early supporter of the Legal Rights Centre. "He'd be filing motions five, vi at a time on a traffic case."

"Some lawyers will spend well-nigh of their fourth dimension in the back room trying to convince not just their client but also the prosecutor to brand a deal—Keith was kind of the opposite. He'd exist filing motions v, six at a fourth dimension on a traffic case."

Ellison's aspirations every bit a community leader led him into an alliance with the Nation of Islam. If reclamation was the idea animating Ellison as he entered his 30s, Farrakhan was black America's leading evangelist for it, commanding huge crowds for speeches that could concluding hours. In 1995, Ellison and a small group of pastors and activists he'd worked with on policing issues (including the leader of the local NOI chapter) organized buses to accept black men of all religions from the Midwest to nourish Farrakhan's Million Human being March.

In his volume, Ellison describes the event, held in October 1995, as a turning point in his flirtation with Farrakhan. Later on filling those buses and attending the march, he was struck by the smallness of Farrakhan's message compared with the moment. The spoken communication was rich in masonic conspiracies and dishonest numerology about the number nineteen. What was the point of organizing if information technology built up to nothing? Ellison says he was reminded of an old saying of his father's, which is attributed to former House Speaker Sam Rayburn: "Any jackass can kicking down a barn, but it takes a carpenter to build one."

Ellison has said that he was never a fellow member of the Nation of Islam and that his working relationship with the arrangement'southward Twin Cities study group (the national arrangement's term for its capacity) lasted simply 18 months. He has said that he was "an angry immature black man" who thought he might have found an ally in the cause of economic and political empowerment, and that he disregarded Farrakhan's nigh incendiary statements considering "when you're African American, at that place'southward literally no leader who is not beat out up by the printing." In his book, Ellison outlines deep theological differences between the group and his mainstream Muslim organized religion. But his break from Farrakhan was not quite every bit clean as he portrayed information technology. Under the byline Keith Ten Ellison, months after the march that he described as an epiphany, he penned an op-ed in the Twin Cities black weekly Insight News, pushing back confronting charges of anti-Semitism directed at Farrakhan. In 1997, nigh ii years later, he endorsed a statement again defending Farrakhan. When Ellison ran (unsuccessfully) for state representative in 1998, Insight News described him as affiliated with the Nation of Islam. Ii organizers who worked with him at the time told me they believed Ellison had been a fellow member of the Nation. At community meetings, he was even known to testify up in a bow tie, accompanied by night-suited members of the Fruit of Islam, the Nation's security wing.

Minister James Muhammad, who in the 1990s led the Nation of Islam'south Twin Cities report grouping, confirms that Ellison served for several years equally the local grouping's principal of protocol, interim as a liaison between Muhammad and members of the community. He was a "trusted fellow member of our inner circle," says Muhammad, who is no longer active in the Nation of Islam. Ellison regularly attended meetings and sometimes spoke in Muhammad's stead, when the leader was absent-minded. An Ellison spokesman declined to answer questions about the congressman'due south role in the report group and instead replied in an email, "Right wing and anti-Muslim extremists take been trying to smear Keith and misconstrue his record for more than a decade. He'south written extensively about his piece of work on the Million Man March, and has a long history of standing up against those who sow division and hatred."

Information technology was just in 2006, as his run for Congress floundered, that Ellison repudiated Farrakhan. "I was hoping information technology wouldn't come upward," he told the Star Tribune, when pressed. In a letter to a Jewish customs arrangement, he conceded that Farrakhan'southward positions "were and are anti-Semitic, and I should have come to that conclusion before than I did." Now he considers the matter settled. Last fall, his aides canceled a scheduled interview with the New York Times when they were told that questions about Farrakhan would exist raised.

His break from the Nation of Islam'south Louis Farrakhan was not quite as clean every bit Ellison has portrayed it.

Critics in the Twin Cities view the human relationship in cold political terms—Farrakhan was a useful affiliation for Ellison up until he wasn't. "Keith was able to climb up some steps by talking about his respect and dear for the honorable government minister," says Ron Edwards, a Minneapolis media fixture and a former director of the radio station where Ellison co-hosted his show. "People don't forget that." Spike Moss, an organizer who worked with Ellison on the Meg Human March, called his reversal "the ultimate betrayal." Farrakhan even recorded a Facebook video responding to Ellison this by December. "If you lot denounce me to achieve greatness," he said, "wait until the enemy betrays yous and and then throws you back similar a piece of used tissue paper to your people."

Menakem attributes the various identities that his book club buddy and radio co-host adopted over the years—Keith Hakim, Keith X Ellison, Keith Muhammad—to "him becoming conscious and him trying on dissimilar ways of being before he settled on who he is," he says. "He's ever remaking himself," says Anthony Ellison, the congressman'due south younger brother. "The Keith Ellison from xx years ago is non the Keith Ellison today."

After a decade generally working outside elected politics, Ellison says he decided to run for the state House after testifying at a hearing on sentencing reform and seeing no blackness legislators. "We oft had these debates and discussions about 'out of the streets and into the suites'—that was the term that was used to describe the swan vocal of the civil rights motility," says August Nimtz, ane of the few black professors at the Academy of Minnesota and a longtime associate of Ellison's. "He made a decision and thought he could make a difference by being on the within." Subsequently a false kickoff in 1998, he won election as a land representative from Northward Minneapolis on his second attempt in 2002. A few years afterwards, he jumped into the race to succeed retiring Democratic Rep. Martin Sabo in 2006.

In a field that included a one-time state party chair and a candidate supported past Emily's List, Ellison had to notice his own base amongst a steady trickle of stories about his by. One Minnesota political newsletter declared him a "expressionless man walking." Ellison labored to show Jewish progressives he'd turned a folio. He picked up the endorsement of the American Jewish World, the Twin Cities-based newspaper, and he addressed voters' concerns about Farrakhan at the state'due south largest synagogue. Ellison's years of organizing and legal piece of work formed the footing for a coalition. Fashioning himself as a lefty in the mold of progressive icon Paul Wellstone, Ellison adopted the late senator's spruce-light-green campaign colors and railed against the "Republican lite" leaders of his party. He ran against the Republic of iraq War and pushed for unmarried-payer wellness care. As well critical was the mobilization of a new constituency in the Twin Cities—Muslim Somali Americans, who had begun settling in the area in the 1990s.

In that first chief, Ellison embraced the old-school tactics he aims to bring to the DNC. He ran no campaign ads; instead, he invested in paid community organizers who started their work early, months before a traditional campaign might lumber to life. Ellison often accompanied his organizers on their rounds. They targeted apartment buildings housing immigrants—Russians, East Africans, Latinos—who had picayune history of political engagement, and they recruited organizers who came from these communities. "Yous go to Keith'south campaign function and information technology looks like the Un," says Corey Day, the executive director of the state Autonomous-Farmer-Labor Party. The Minneapolis City Pages called his coalition "the most diverse crayon box of races and creeds a Minnesota politician has e'er mustered."

Ellison's district is so blue he hardly needs to campaign to ensure reelection. Only he views constant voter contact, during the election and afterward, every bit essential to his agenda. He cites research showing that just 58 percentage of self-identified liberals vote, versus 78 percentage of cocky-identified conservatives. If a country party tin can juice that 58 percent merely a little, he argues, it tin defeat ballot initiatives and keep its grip on statewide offices. Solar day credits Ellison'south organizers with beating back a Republican voter ID initiative in 2012. Michael Brodkorb, a Republican operative who unearthed some of the nearly damaging stories most Ellison in 2006, views Ellison's become-out-the-vote machine with awe: "He turned political organizing into what I think most people think political organizing is."

"He turned political organizing into what I recollect most people call back political organizing is."

Heading to Washington marked another change in Ellison'south political identity. In St. Paul, "I don't think more than a scattering of close friends of his even knew he was Muslim," Dave Colling, who managed his first congressional campaign, told me. Ellison shied away from discussing his religion during the race, telling reporters it was "non that interesting." But as the first Muslim representative ever elected to Congress, a rising tide of conservative religious nativism ensured that his faith would remain front and heart.

Later Ellison told a Somali American cable-access host that he intended to be sworn into office on a Koran (he used Thomas Jefferson's personal copy), Rep. Virgil Goode, a Virginia Republican, warned there would "likely be many more Muslims elected" unless his colleagues "wake up." Glenn Beck asked the congressman-elect during an interview to "testify to me you are not working with our enemies." The innuendo did non get away with time. In 2012, after they had been representing neighboring districts for five years, then-Rep. Michele Bachmann accused Ellison of working with the Muslim Alliance. When Rep. Peter Rex (R-North.Y.) held hearings on Muslim "radicalization" in the The states in 2011, Ellison testified in defense of his religion, crying as he recounted the story of a Muslim paramedic who died in the Globe Trade Center assault only to be posthumously smeared as a terrorist accomplice.

Ellison was thrown into some other maelstrom when, in the fall of 2015, Minneapolis law shot and killed Jamar Clark, a 24-year-erstwhile unarmed black man, every bit he lay handcuffed on the ground. After Black Lives Matter protesters began an occupation at the fourth police precinct headquarters, Ellison flew abode to meet with them. At first, he backed the encampment. With the city on border, he moved easily between dissimilar groups, negotiating a meeting betwixt Clark'southward family and the Democratic governor, Mark Dayton.

For more than a week, Ellison hung with the BLM organizers, even equally the Minneapolis Star Tribune published a photo of Ellison'due south center son, Jeremiah, with his easily upwardly while a policeman pointed a gun in his direction. (Ellison called the photograph "agonizing.") Just afterward a white man opened fire* on the mostly blackness protesters, injuring five people, Ellison finally broke with the demonstrators and supported the mayor'due south phone call to relocate the encampment for public rubber. Debating with activists on Twitter, he insisted he was merely proposing a change in tactics; the goal had stayed the same. Minneapolis NAACP President Nekima Levy-Pounds, filling the role Ellison one time played of the organizer chipping away at the arrangement from the outside, dismissively referred to him every bit "the old guard," and protesters held signs calling him a "sellout." When Ellison showed up at a North Minneapolis community meeting to explain himself, Levy-Pounds refused to give him the floor and Ellison left without speaking. "Information technology was essentially the establishment versus the community," Levy-Pounds says. Ellison had crossed over.

In the run-up to the 2016 election, Ellison recognized the Democratic Political party was at a crossroads. With a message that foreshadowed his DNC entrada, he traveled the state imploring Democratic groups to become back to organizing. Toting a voter-turnout manifesto called "Voters First," he barnstormed places where the party was desperate for a jump-start, like Utah and Nebraska. But he also made his pitch to party insiders at the DNC's summer meeting in 2015, just as the Democrats were powering upwards their 2016 election machinery, led by a network of allied super-PACs. Implicit in his message was a critique rooted in his experience in Minneapolis: Democrats focus also much on fundraisers and not enough on organizers. They provide lip service to the working grade while fêting elites. The political party's losses in November have reinforced Ellison's conventionalities.

Clara Wu

In laying out his platform, Ellison, who has promised to footstep downwardly from Congress if he wins, acknowledges a rot within the political party. Information technology has lost more than 900 state legislative seats since 2008, and the problem is cocky-perpetuating; those losses mean Republicans control redistricting, which means Democrats lose even more seats, which means they have fewer candidates to run for higher office, and so on. Quondam DNC Chair Howard Dean, facing a similar quandary, proposed a 50-country strategy; Ellison is offering "a 3,143-county strategy."

Political party chairs reflect the ethos of their fourth dimension. Dean followed the wave of the progressive Netroots; Tim Kaine mirrored the hope and dad jokes of Barack Obama. Ellison'south candidacy and the intensity of the progressive groups backing it are in many ways a continuation of the concluding state of war, between Bernie Sanders and Hillary Clinton, who the Vermont senator'due south supporters claim was unfairly aided by the Autonomous establishment. Ellison'south closest rival, Perez, is backed by Clintonites. But the frame elides the similarities betwixt the two. Perez, like Ellison, was a civil rights lawyer, and he retooled the Justice Department'southward Civil Rights Partitioning to refocus on voting rights and law abuses. They aren't far autonomously politically, and their prescriptions for healing the party aren't too dissimilar either. When it comes to the DNC, their biggest deviation may be that Ellison supports a ban on accepting money from lobbyists and Perez doesn't. (But Ellison says he won't press the issue if DNC members oppose it.) Ellison wants the DNC to get a greater share of its funds from minor-dollar donors, and he has committed to acquiring Sanders' historically lucrative email listing for the party if he wins. Perez would like that list, too, of grade, just Ellison, by virtue of his shut relationship with Sanders and trust among the political party's left wing, might stand a better adventure of both getting it and knowing how to deploy it.

He is pledging to bring voters who accept non been active in Democratic Party politics into the fold, just like he's done in Minneapolis. "Nosotros've got to requite Blackness Lives Thing a place where they can limited themselves electorally," he said in Dec, while in the same breath urging the party to cast aside tired assumptions almost voters in the Midwest: "Can we not say 'Rust Belt' anymore? Look, I'one thousand from Minnesota—I don't feel rusty." Rep. Raúl Grijalva of Arizona, who co-chairs the progressive conclave with Ellison, says his colleague's forcefulness is in rallying diverse factions around a mutual narrative. "He can talk almost his life experience. He tin can talk about what information technology's like to stand for and be function of a multicultural, multiracial, multi-consequence kind of a political activism."

Choosing Ellison to pb the Democratic Party would exist a gamble. It would hateful going all in on a diagnosis that says the party's shortcomings in recent years are not due to a rejection of liberalism by voters, but because the party has not been liberal enough. It might alienate a minor but influential faction of Autonomous leaders, such as Haim Saban. (At a argue featuring DNC candidates in January, Ellison said he and Saban had spoken and "we're on the route to recovery.") Still, Ellison is betting big on his easily-on formula. If Democrats do the work, he reasons, they but might be able to reverse their losses and conductor in a new era of post-Trump progressivism. In the get-go days of the Trump administration, it looks similar a long shot. Simply stranger things have happened.

Additional reporting by Ryan Felton.

* Correction: This story originally misstated the number of shooters at the 2015 Minneapolis protest.

Source: https://www.motherjones.com/politics/2017/02/keith-ellison-democratic-national-committee-chair/

0 Response to "Keith Ellisons Plan for Democrats to Win Again You Tube"

Post a Comment